Bosque Redondo Memorial

Fall 2021 Member News Feature

Truth and Reconciliation: A New Beginning at Bosque

Several years ago, across a crowded room in Santa Fe, Mary Ann Cortese heard the sound of weeping. When Cortese, a Museum of New Mexico Regent, agreed to take part in a series of dialogues about the Bosque Redondo Memorial’s plans for a new permanent exhibition, she expected that emotions would run high. After all, the room contained a group of people with vastly different interests and backgrounds who were there to discuss a particularly painful period in New Mexico history.

Seated at small tables were state Department of Cultural Affairs officials, Historic Sites staff, historical research associates, and tribal leaders from the Navajo (Diné) and Mescalero Apache (N’de) communities. Over the past three decades, their collective goal to launch a different narrative at Bosque Redondo had hit more than a few roadblocks.

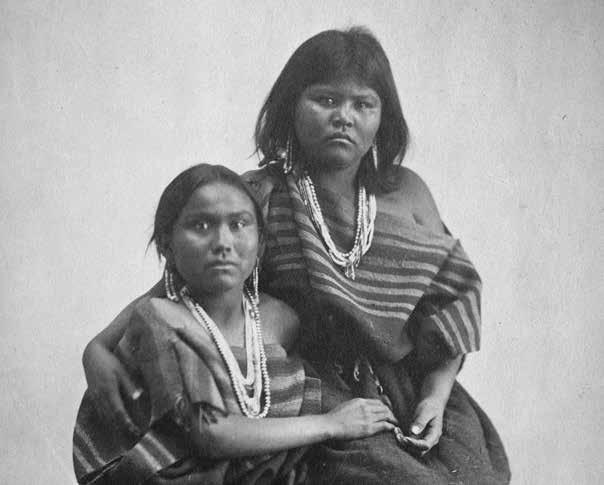

“Why don’t you tell our story?” asked a letter left at the Fort Sumner-based memorial in the summer of 1990, setting the idea in motion. The question came from 17 visiting Navajo students who felt their ancestral trauma had been erased from the historical record. For nearly 30 years—and even after the opening of the Bosque Redondo Memorial in 2005—Historic Sites staff had been striving to more fully and accurately tell that story at the site.

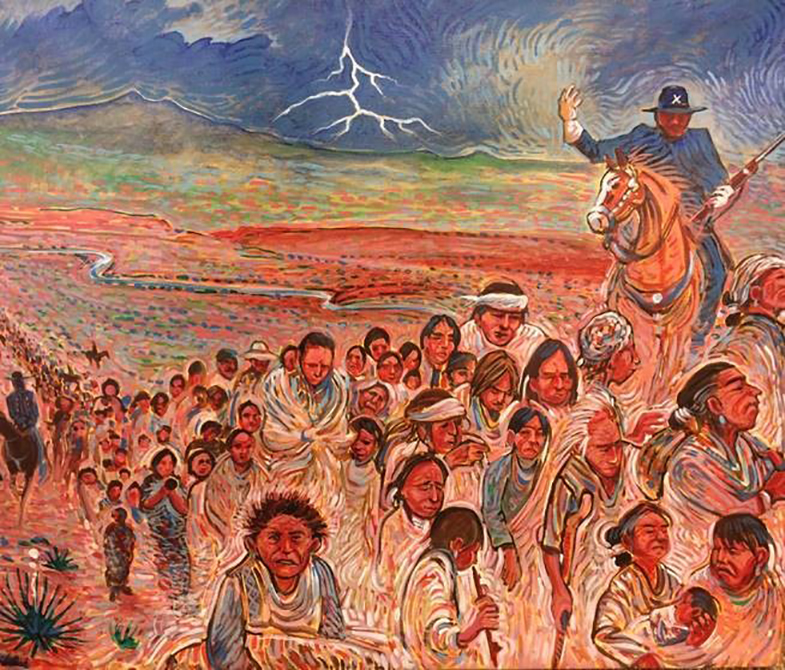

By 2017, everyone in the room with Cortese had agreed to install an updated exhibition about the Long Walk, the United States government’s forced and violent relocation of Navajo and Mescalero Apache peoples across more than 400 miles between 1863 and 1868. Over those five years, 9,500 Navajo and 500 Mescalero Apache were tortured and imprisoned by the Kit Carson-led U.S. military on the Bosque Redondo Reservation.

With that difficult history in mind, Cortese says she was all the more struck by what she saw in the meeting that day. “We heard crying, and turned and looked. There were two ladies hugging one another. One had a Navajo ancestor from the Long Walk, and the other was a descendant of one of the soldiers. They had come to an agreement on how they felt about it with each other.

“We had a lot of moments like that, building up to where we are today,” Cortese says.

From Erasure to Awareness

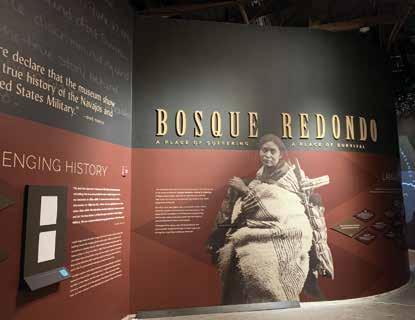

On Indigenous Peoples Weekend, October 8-10, the new exhibition, Bosque Redondo: A Place of Suffering, A Place of Survival, opens at the Bosque Redondo Memorial at Fort Sumner Historic Site.

In the lead-up to the unveiling, a few key players in its long evolution reflected on the road behind them. Their journey includes more than one scrapped plan, several key funding opportunities and an important period of reconciliation along the way.

For Carlota Baca, a former Museum of New Mexico Foundation trustee, it began with a revelation. While serving as co-chair of the Foundation’s development team for what was then the New Mexico State Monuments division, Baca made her first “eye-opening” visit to Bosque Redondo.

“I felt so sad that I had never heard of what happened there. I was staggered by the fact that I never knew,” says Baca, an Albuquerque native. “I remember walking around and someone muttered, ‘My God, this was the Navajo Holocaust.’”

Baca’s emotional experience at the memorial helped jumpstart the push to better educate site visitors. Another touchstone was the Bosque Redondo Memorial’s 2005 designation as an International Site of Conscience—one of 175 in the United States. These sites honor the need to remember places where atrocities occurred, even in the face of pressure to forget unpleasant histories.

Former State Representative George Dodge Jr., who served in the New Mexico Legislature from 2011 to 2019, was familiar with the history of the Long Walk from teaching it to middle schoolers in Santa Rosa. But even in his New Mexico history classes, he admits, “I never really went into depth with the students about it. There was never enough time.”

A visit from Cortese after Dodge was elected to the legislature changed all of that. When he toured the memorial site, he realized the importance of funding a new exhibition.

“I wanted to see that memorial flourish and see it expanded to its fullest potential. We have to make sure the story’s being told correctly,” he says. He met with Foundation members, Friends of the Bosque Redondo Memorial, Department of Cultural Affairs staff and State Senator Stuart Ingle to see what could be done. Through annual capital outlay requests during his legislative tenure, Dodge helped secure as much as $100,000 in annual funding for Bosque Redondo.

Other funding would follow, including a $150,000 challenge grant through the Foundation from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Creating Humanities Communities program. The matching grant generated $300,000 for the Bosque Redondo Memorial. A portion of these funds will support interactive exhibition programming.

When Truth Met Reconciliation

By the end of 2015, with enough funding to move forward with one of two different conceptual exhibition designs, the most crucial element was still missing: participation by the Native communities whose histories the site aimed to tell.

“We had the money,” site manager Aaron Roth remembers. “We were faced with the question: do we spend it on an exhibit that is not agreed upon or approved or designed by our tribal partners? Or do we take it back to the beginning?”

With the unanimous agreement of State Historic Preservation Officer Jeff Pappas, former Department of Cultural Affairs Secretary Veronica Gonzales and Historic Sites Director Patrick Moore, the team went back to the drawing board.

This time, as many people as possible took a seat at the table. Over what Roth describes as a yearlong series of collaborative sessions, a new plan took shape.

Among the tribal participants was Manuelito Wheeler (Navajo/Diné), director of the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock, Arizona. Noting that an earlier proposal had centered the Fort Sumner story on “the pioneer experience,” he says that, gradually, he came to realize that the newly proposed exhibition was going in the right direction.

“I was definitely skeptical in the beginning,” Wheeler says. “As we progressed, I really felt more enthusiastic. Finally, there was going to be this more accurate story.”

Conflict mediator and consultant Tammy Boorman, who was sent by the International Sites of Conscience to facilitate discussions in both 2007 and 2017, says the 2017 meetings were all about “learning on an interpersonal level.”

“To have folks coming together around the table in different power dynamics—the state, senior tribal leaders, historians, external experts like historical research associates, interpretive planners—the group had to be very intentional,” she says. “That made a difference the second time around.”

Boorman recalls the particularly powerful moments when tribal partners welcomed the participants to Bosque Redondo, Window Rock and the Mescalero Apache Reservation, among other locales.

“In Navajo cosmology, returning to the land of trauma, to visit a memorial that is literally built on the bones of your ancestors, is not something you do very easily,” she says. “Apart from the work we were doing, there was a tremendous amount of spiritual and emotional energy when we were on-site.”

Wheeler explains the situation from a tribal perspective. “There are varying versions of how Fort Sumner should be approached. The more known Navajo belief is that Fort Sumner should never be visited and never discussed. In terms of a psychological reason behind that, of course that was such a horrific point in Navajo and American history. There’s a reason not to want to revisit that.

“But there’s plenty of Navajo people who are still traditional, but through prayer and ceremony and respect, are okay with visiting the site as well,” Wheeler continues. “A significant number of the visitors to the Bosque Redondo Memorial are Native people. Navajo people are still feeling a pull to visit Fort Sumner. Some of it may be for healing on their own, to understand that trauma. Other people are wanting to visit to gather strength because we as Navajo people, a lot of us are direct descendants of people who were held prisoner at Fort Sumner. Because of our ancestors’ strength, we’re here today. Visiting the site is a spiritual way to gather that strength and honor our people.”

Amid the sea of collaborators, a few individuals stand out. Roth singles out Holly Houghton (Mescalero Apache), Historic Preservation Officer for the Mescalero Apache tribe, as instrumental in the communication process.

“Holly has been with the project since the nineties. I know that, even from her perspective, it was a little disheartening how long it took,” Roth says.

Cortese cites the 2006 death of Bosque Redondo Memorial advocate John McMillan. He met with Navajo leaders about the site as early as 1995, as an incentive to push forward.

“Even from his hospital bed, he was giving instructions,” she recalls. “He said, ‘No doesn’t mean no, it just means maybe.’”

After the Pandemic, a New Chapter Unfolds

When COVID-related closures delayed the long-anticipated opening of the exhibition by more than a year, Roth and Cortese saw an opportunity. The exhibition was nearing completion, but something was still missing. According to Roth, the exhibition wasn’t ending in just the right way.

“You’ve come through the entire experience, you’ve learned about life after the signing of this treaty, and then you’re fed back through the rotunda. It didn’t really bookend the experience,” he says.

The final touch is the newly added “decompression room,” a space where visitors can sit and reflect on the enormity of what they have just learned.

“It’s a heavy burden when you come out of the exhibition,” Roth says. “Even when we had panels and it wasn’t interactive, people would come out of that space crying or with lots of questions. There needed to be something deeper. It’s a space to ponder, to consider what you’ve been through, to have a discussion with your family or the rangers.”

Project partners and exhibition designers embraced the new space. Half of the room is dedicated to six other International Sites of Conscience partners—global sites with similar histories of wrongful incarceration or atrocities committed on Indigenous peoples.

As the exhibition is unveiled this fall, so many who shepherded the project believe the delays occurred for a reason. “Every pause gave us a chance to redevelop and improve things,” Roth says. Cortese adds, “Had any of the other designs gone through, they wouldn’t have been correct. This is exactly what should have happened.”

“It’s been a whole lot of fits and starts,” says Dodge. “But that’s understandable. I’m just glad it’s finally here.”

“From an exhibit standpoint, that whole place has been transformed,” says Wheeler. “You’re going to be seeing a whole new museum there. There are state-of-the-art interactives. It’s a top-tier museum experience. The emotional punch is absolutely there, as it should be, because it is such a powerful point in Navajo and American history.”

For Baca, the Bosque Redondo project ls a powerful beginning of a new chapter for New Mexico Historic Sites.

“I hope that this opening enhances the advocacy and the interest in historic sites,” Baca says. “A lot of New Mexicans, unless they live where there is one, they just have no idea what happened there.”

Bosque Redondo A Place of Suffering, A Place of Survival

To support the New Mexico Historic Sites, contact Yvonne Montoya at Yvonne@museumfoundation.org or 505.216.1592.

Public Opening: Spring 2022

Where: Fort Sumner Historic Site/Bosque Redondo Memorial

3647 Billy the Kid Drive, Fort Sumner, NM 88119

Information: 575.355.2537

Visit: nmhistoricsites.org/bosque-redondo

Connect