Full Circle: Honoring 100 Years of Indian Market

We often hear of events coming full circle, cycling back to where they came from. That’s certainly the case with Honoring Tradition and Innovation: 100 Years of Santa Fe’s Indian Market 1922–2022, opening to the public August 7 at the New Mexico History Museum.

With the commemoration of Indian Market’s first century, the Southwestern Association of Indian Arts returns to a collaboration with Indian Market’s original organizer: the Museum of New Mexico. Overseeing Indian Market during its first five years, the museum system played a significant role in developing what is now the world’s largest Native art market.

Museum of New Mexico founder and director Edgar Lee Hewett helped create Indian Market with artist-archaeologist Kenneth Chapman in 1922. Cathy Notarnicola, the history museum’s curator of Southwest history, says Hewett and Chapman rolled the first market into their (also newly created) Santa Fe Fiesta celebrations. But their intentions went beyond providing a venue for Indigenous artisans to sell their works. Notarnicola describes their main goal as “an attempt to try to revive and perpetuate Native-made goods” within the larger Pueblo Revival makeover of Santa Fe, which began in earnest in the 1920s.

Hewett and Chapman, among other Anglo museum professionals, felt that older styles of Pueblo pottery and sculpture were falling out of fashion in the early 1920s. Thus, the first Indian Market, held indoors with prizes awarded, was an attempt to influence artists to create more traditional artworks.

“The people running the Indian Market,” Notarnicola explains, “were encouraging artists to make the old style of pottery that was more utilitarian and larger, like storage and water jars, versus the small curios that were being sold as souvenirs.”

Though Indian Market is now run by a primarily Native staff and board members, Honoring Tradition and Innovation does not shy away from its problematic origin story of white museum professionals curating an Indigenous art market. Nor does it dodge any other histories, difficult or otherwise.

For example, Indian Market organizers, in conjunction with area Pueblo Indian leaders, were instrumental in helping to defeat the Bursum Bill in the U.S. Congress in 1923. The bill would have allowed non-Native people to claim Pueblo Indian lands. Honoring Tradition and Innovation traces these larger stories while celebrating the career paths of individual artists via Indian Market, where they received honors and notoriety. The interactions between artists and collectors that make the market such an enduring attraction, Notarnicola says, are also a common thread that runs through the Indian Market story.

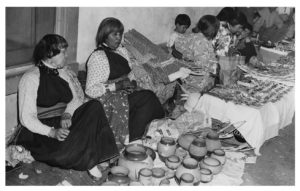

The exhibition features more than 200 works by Indian Market artists, drawn from private and public collections, along with featured interviews with artists and collectors. More than 100 historic and contemporary photos, including photos of early markets sourced by Palace of the Governors Photo Archives curator Hannah Abelbeck, are also featured.

The exhibition begins with a giant graphic of an 1880 train stopping in Laguna Pueblo. “Tourism flourished once the train started coming through,” Notarnicola says. “Artists were making these figures in reaction to that. And then you’ll see a re-creation of the first Indian Market from that.”

Honoring Tradition and Innovation cycles through the century, pausing to spotlight influential artistic families, including the Tafoya (Santa Clara Pueblo) and Martinez (San Ildefonso Pueblo) clans. Important policy decisions (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act and the Indian Arts and Crafts Act) and debates about what is “authentic” Native art are also explored.

A final section on the future of Indian Market benefits from the Indigenous Futurism of Cochiti Pueblo artist Virgil Ortiz, who presents his multimedia vision of evolving Indian Market art via his science-fiction series Revolt 1680/2180.

Over the exhibition’s yearlong run, programming will include a lecture series featuring Ortiz and artists in various Indian Market genres. Private funding is needed for honoraria for lecture guests, as well as for artists participating in the interview series that accompanies the show.

Due to staffing shortages, Honoring Tradition and Innovation’s installation also cost more than its original budget. Despite the difficulties, Notarnicola is firm about the significance of remembering 100 years of Indian Market with an exhibition of this caliber.

“What happens at this market is really important. It’s not just exchanging money. It influences the Native art world,” she says. “There are real friendships and relationships being formed, which last for decades.” Or, more precisely, a century and counting.

To support exhibitions and public programs at the New Mexico History Museum, contact Yvonne Montoya at 505 215.1592 or Yvonne@museumfoundation.org.

This article is from the Museum of New Mexico Foundation’s Member News Summer 2022.

Image of Pueblo pottery vendors on the Palace of the Governors portal during Fiesta, Santa Fe, 1948. Photo by Robert H. Martin, courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), neg. no. 041392.

Connect