Celebrating the Palace: Past, Present and Future

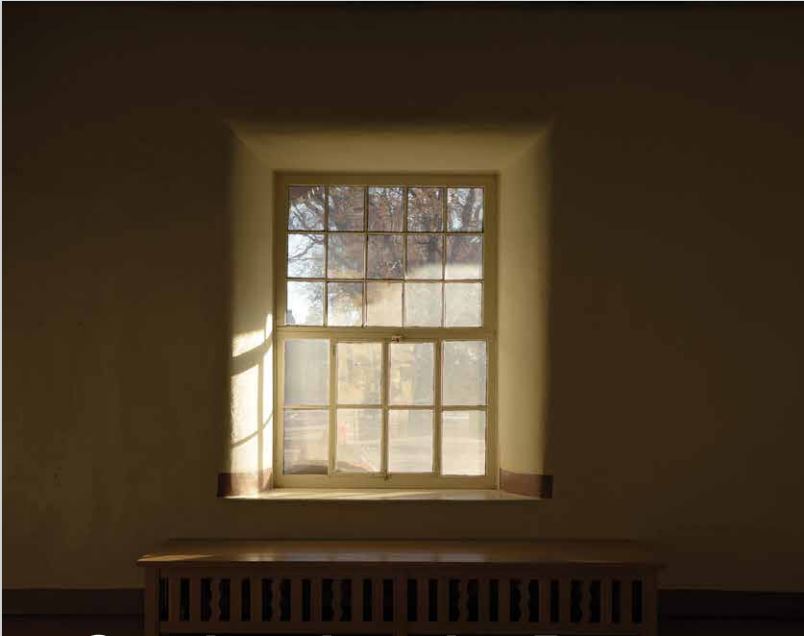

Sunlight pours through the windows at the Palace of the Governors, New Mexico’s most historic public building. Located across the street from the Santa Fe Plaza, the Palace was built in 1610 as the seat of Spanish colonial government, but changed hands many times over the centuries. Designated as the state’s history museum in 1909, and named a National Historic Landmark in 1960, it is the oldest building in the United States, built by Europeans, still in continuous use.

Today, the 20,000-square-foot adobe structure is part of the New Mexico History Museum campus. In addition to its architectural significance, the Palace is perhaps most famous for the Indigenous artists who sell their work under the exterior portal, which stretches the length of the building along Palace Avenue.

Beginning in 2018, the Palace interior underwent a massive rehabilitation that expanded exhibition space by more than 2,300 square feet, and all galleries are now open to the public. The Palace’s bright white walls and freshly finished floors welcome visitors into the structure’s grandeur, which was hard to perceive in the formerly dim spaces created during a 1970s renovation.

“It was more like a stage set than a museum, with many non-historical elements,” says executive director Billy Garrett, who joined the museum in 2019. An architect with expertise in historic architecture and cultural anthropology, Garrett served as a county commissioner for Doña Ana County from 2011–2018. “The treatment that we’re using is called rehabilitation—historic preservation terminology that means keeping the building in use while maintaining its historic character and features.”

The past, present and future of the Palace will be celebrated at the New Mexico History Museum on Saturday, April 20, in an event highlighting New Mexico’s cuisine, creativity and cultural treasures.

“We are so excited to mark the grand unveiling of the Palace of the Governors after years of extensive renovation,” says Jamie Clements, president and CEO of the Museum of New Mexico Foundation. “Our guests will discover beautifully restored and enhanced interior spaces with new exhibitions that will tell the 400-year-old history of the Palace and its important role in our state’s development and governance.”

Preserving the Palace

As in any well-preserved historic home in Santa Fe, architectural and design features from different eras and residents commingle in the Palace. One room leads to the next and then the next, added over time as space was needed. The rehabilitation revealed covered-over windows and doorways that are now in use, some functionally and some as artifacts. A set of panoramic murals depicting Puye cliff dwellings, originally painted in 1910 by Swedish artist Carl Lotave, were cleaned and restored by Bradford Epley, head of conservation for the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs.

Cathy Notarnicola, the museum's curator of Southwest history, finds the rehab especially impressive for the way it opened the sightline through the galleries. “If you’re on one end, you can see all the way through to the other end,” she says. “It seems gigantic compared to the past, when rooms were cut off and windows were darkened to protect hide paintings on the walls.”

Although the Palace received upgraded fire suppression and HVAC systems, curators must be careful about the effect of natural light and dry air on the objects they’re charged with preserving for future generations, Notarnicola explains. The bison-hide works, known as the Segesser Hide Paintings, that once hung on Palace walls are now exhibited in the climate controlled Domenici building, behind the Palace on Lincoln Avenue. And the 50 bultos and retablos in The Santos of New Mexico installation in the Palace are regularly rotated with others from the Larry and Alyce Frank Collection to protect them from the elements.

Metal items fare better in the Palace climate, such as the unusual sea creatures in Silver and Stones: Collaborations in Southwest Jewelry, featuring pieces made by David Taliman, a Diné silversmith, for Ilfeld’s Department Store in 19th-century Las Vegas, New Mexico. A new exhibition, 18 Miles and That’s As Far As It Got: The Lamy Branch of the Atchison, Topeka and

Santa Fe Railroad, features a 32-foot re-creation of the train, meticulously crafted by the Santa Fe Model Railroad Club, that ran between Lamy and the capital city during the 1940s.

The New Mexico Food Heritage Program, a three-year exhibition opening in spring 2024, is sure to inspire similar enthusiasm. Curated by the popular Santa Fe chef Johnny Vee in a renovated gallery space that most recently served as a museum shop, this highly anticipated exhibition celebrates New Mexico ingredients like corn and chile, as well as quintessential dishes, historic restaurants, and top chefs who are carrying on traditions and innovating new ones.

“We’ll have a speaker series, and special dinners and tastings. We’ll extend into the courtyard for tortilla-making demonstrations. We’ll offer take-home recipe cards,” Vee says. “What I wish is that we could figure out a way to have people be able to smell sopaipillas, smell carne adovada.”

Contemplating Complexity

The Palace of the Governors is more than a museum: it is itself a historic object. For many New Mexicans, it’s a place of pride that honors their familial connections to their Spanish and Mexican forebears. For others, it’s a site where their Indigenous ancestors experienced violence and oppression.

The Palace: Seen and Unseen exhibition explores these multiple identities through the building’s archaeological history. The exhibition includes text panels about the different eras, from Spanish colonial occupation through the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, after which various Pueblo peoples transformed the Palace into a high-walled fortress and made it their home. The story continues with the Spanish reoccupation of the Palace in 1693, followed by a period of Mexican rule (1821–1848), settlement as an American territory (1848–1912), and New Mexican statehood in 1912.

Visitors can peer through plexiglass panels at the building’s foundations, uncovered during excavations, and trace different configurations of the room through stain patterns on the floor. The exhibition is on display through 2030 and will be continuously deepened and expanded.

“We can create a space for people to contemplate the age of the building and all of its associations,” Garrett says. “This was the edge of the Spanish empire. This was a colonial capital. There was a high level of stratification within society, and different kinds of relationships with Native peoples, not all of which were positive. This building represents a lot of different things. We want to help people understand the complexity.”

This article and image are from the Museum of New Mexico Foundation’s Member News Magazine.

Connect