Form and Practice: The Vladem Contemporary Connects Old and New

The passage of time renders old what was once new.

Consider the New Mexico Museum of Art, which opened in 1917 to showcase contemporary works made by living artists. Robert Henri, Gerald Cassidy and Kenneth Chapman were among the first to contribute paintings to the museum’s collection, creating works specifically for the new Pueblo Revival-style building on the northwest corner of the Santa Fe Plaza.

Today, explains Mark White, the museum’s executive director, “Those same paintings are considered modern, rather than contemporary art.”

The collection has grown tremendously since 1917. But the museum—a devoted guardian of the older works—is nearly out of space for new acquisitions. Just as pressing: the Plaza building’s technological capabilities don’t serve 21st-century artists. Indeed, no one could have anticipated LED light installations or live-streamed performance art in 1917, or even in 1980, when the Plaza building was expanded. These limitations have imperiled the museum’s founding mission.

Until now. When the New Mexico Museum of Art’s Vladem Contemporary opens in the Santa Fe Railyard this September, the museum will embrace and engage anew the artistic frontiers envisioned by its founders.

There’s no ideological or aesthetic division between the sites. As a whole, the new Railyard building and the original Plaza building should be considered two wings of the same Museum. “We’ll be able to show contemporary art in a more versatile way,” White says.

Preserving Community History

The two-story Vladem Contemporary on the corner of Guadalupe Street and Montezuma Avenue is one of the Railyard District’s most historic structures. The original ground-floor section was erected in 1936 next to the train depot, on the site of an old coal field. It was a warehouse for the Charles Ilfeld Company, which closed in 1959. The New Mexico State Records Center took over the building in 1960, and when its longtime director Joseph Halpin died in 1987, the building was renamed in his honor.

The New Mexico State Records Center moved to a state-of-the-art facility in the 1990s, and the state Department of Cultural Affairs began using the Halpin Building for storage and office space. In 2013, plans to store some of the New Mexico Museum of Art’s ever-expanding collection there soon transformed into plans for a new museum building.

In 2016, as the museum prepared for its 100th anniversary celebration, the Museum of New Mexico Foundation kicked off a $12.5 million Centennial Campaign to enhance its public-private partnership with the State of New Mexico and support the museum’s vision for a second location.

“We were equal partners in funding the construction, to the tune of about $10 to $11 million each,” says Jamie Clements, the Foundation’s president and CEO. “The state contribution came through capital outlay appropriated by the state legislature. In addition, the state has added $1 million in annual operating funds for the Museum of Art to accommodate the additional staff needed for the Vladem. The Foundation, in turn, has raised over $2.5 million for all inaugural year programming for both the Vladem and the 1917 building.”

Robert J. and Ellen R. Vladem made the lead $4 million gift to the Centennial Campaign. “Art changes people’s lives. It affects how they see the world,” Robert Vladem says. “I can’t think of a better way for us to have spent our money. Being a state building, it’s important that you can see amazing things inside the museum, but even more importantly, there will be incredible art installations that you can see from the outside. You can get a daily dose of art without even going into the building.”

The Office of Archaeological Studies performed the site survey before construction began in 2021. Most of the findings were from the railroad era and the area’s days as a coal field. The most significant issue that arose during the planning stages was over the “Multi-Cultural Mural” on the east side of the building, which was deteriorating.

The mural was first painted by a group of New Mexico artists in 1980. It soon began to fade, and one of the artists, Gilberto Guzman, repainted the piece in 1990. Guzman and community activists didn’t want the mural removed as the Halpin Building was remodeled, but the mural was deemed by the state to be too degraded to restore. After a protracted negotiation, Guzman agreed to re-create the mural on several panels, to hang in the Vladem Contemporary’s lobby in perpetuity.

Anatomy of an Art Museum

The Halpin Building was perfectly suited to become an art museum, says Dierdre Harris, senior associate architect with DNCA, one of the two firms that designed the Vladem Contemporary. “The proportions are beautiful and timeless.”

The Halpin Building was perfectly suited to become an art museum, says Dierdre Harris, senior associate architect with DNCA, one of the two firms that designed the Vladem Contemporary. “The proportions are beautiful and timeless.”

Led by DNCA principal architect Devendra Contractor, the design team leaned into Santa Fe’s tradition of masonry load-bearing architecture, preserving the old warehouse rather than tearing it down. The additions, which include a second floor, “honor the old and the new,” says Graham Hogan, principal of the second architectural firm, StudioGP. “It’s a contemporary take on the stuccoed adobe that’s synonymous with Santa Fe.”

The building was expanded from 20,000 square feet to 35,000 square feet, with 4,100 square feet of storage. Harris describes the renovated structure as “two very long bars that have a glass opening in between them, sitting on a concrete base. It’s not exactly proportional.”

Entry is from Montezuma Avenue on the north side, or from the train depot on the south; the two halves of the building are connected by a central lobby. A gift shop on the depot side is connected to the rest of the building by a breezeway that features a permanent LED light installation by the internationally renowned Albuquerque-born artist Leo Villareal.

“He develops patterns based on natural phenomenon—cloud formations, wave dynamics,” says museum director Mark White. “The result often looks like a star field.”

The Montezuma Avenue side of the building is fronted by an eight-by- five-foot Window Box that will showcase installations by New Mexico artists. The first featured artists are Christina Gonzales and Morgan Barnard, members of Vital Spaces, a Santa Fe-based collective that will select artists during the new museum’s first year.

“The windows will be illuminated at night, so there will always be something to see,” White says.

The ground floor contains a 5,000-square-foot main gallery and a new 2,300-square-foot education room for classes, lectures and workshops. “We’ve never had a dedicated education space in the Plaza building, and this is going to be a real art room, where people can do messy projects,” White says. Additionally, the classroom’s east-facing wall is a glass pane onto which artist videos will be projected in the late afternoons and early evenings, visible from the street.

“The Vladem is one of the most innovative contemporary art venues in the country for public-facing art,” says Clements. “There will be outward-facing art projects for all to enjoy, and the opportunity to pass through the central lobby without paying admission.”

Upstairs is over 4,000 square feet of exhibition space and a dedicated artist-in-residence studio. The latter will host five artists each year for two-week residencies that feature public programs. Finally, a rooftop deck with dramatic views of downtown Santa Fe and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains offers a rest area for museum-goers, a gathering spot for art lovers and a singular space for private events.

“We want the Vladem Contemporary to become a social hub in the Railyard, not just for the summer tourist crowd but for the community that lives here 365 days a year,” White says. “We’re hoping to add a lot more to the cumulative energy that’s already present in the Railyard District.”

Building an Artistic Legacy

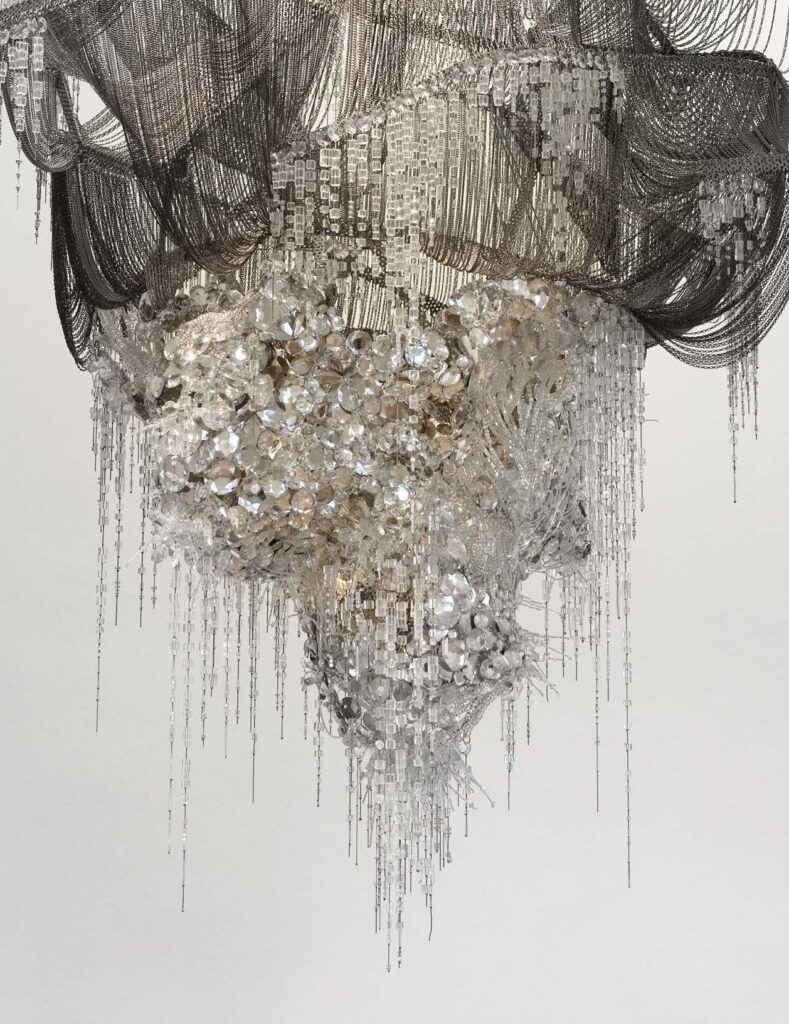

Shadow and Light, the inaugural exhibition at the Vladem Contemporary, features works of sculpture, video, installation, hologram, mixed-media, etching, photography and more by 24 artists, including Judy Chicago, Nancy Holt, August Muth, Virgil Ortiz, Helen Pashgian and Erika Wannemacher. The show contains objects from the museum’s collection as well as pieces on loan from the artists.

While most of the work is by living artists, some are from artists of the past, such as abstract painter Agnes Martin, whose striking and sparse grid patterns had a significant influence on art after 1960.

Shadow and Light “examines the classic idea of New Mexico light influencing artists for generations, how contemporary artists have used light as a physical medium for their work as well as sort of metaphorical construct,” White says.

Christian Waguespack, the museum’s head of curatorial affairs and curator of 20th century art, described the exhibition as an interesting exercise in figuring out where different parts of the collection might belong, particularly as we proceed deeper into the new century.

Christian Waguespack, the museum’s head of curatorial affairs and curator of 20th century art, described the exhibition as an interesting exercise in figuring out where different parts of the collection might belong, particularly as we proceed deeper into the new century.

“I think it’s a nice balance between the older pieces in the collection and how we’re looking at contemporary art being made right now,” Waguespack says. “Contemporary art isn’t a clean cut starting in the 1960s. We saw that there were contemporary pieces that spoke to the kind of trends or concerns in art history that the Plaza building would keep up a bit more robustly. And there were some works from the 1950s that belong with the contemporary work. It got us thinking about what kinds of stories we wanted to tell in each space, what kind of programming we might be engaged in, moving forward. While the collection is one collection, various elements are going to start taking on their own identities in particular ways, which is fun.”

Shadow and Light will be on display through April 2024. After that is Off-Center: New Mexico Art, 1970-2000, which highlights artists who relocated to New Mexico in the last decades of the 20th century, including Larry Bell, T.C. Cannon, Gus Foster and Fritz Scholder. They worked in land art, digital art, minimalism, neo-expressionism and pop art, among other genres that didn’t yet exist when painters first gravitated here. The exhibition will be shown in three rotations throughout the year, in order to capture as much of the thematic breadth of each featured artist as possible. Each installation will include video interviews with the artists.

“In the same way we are responsible for holding the 20th century legacy, we’re very much responsible for holding that artistic legacy moving forward,” Waguespack says. “Although we’re not always going to connect them directly, our exhibitions in both buildings will make connections between pieces that reference historic moments, and pieces that fit into the contemporary moment. The two buildings speak to our history in terms of the art, but the museum was always meant to be a makers’ space, even early in our history. Artists were always supposed to come here to make and exhibit new work. Practice has always been important.

This article and image are from the Museum of New Mexico Foundation’s Member News Summer 2022.

Connect