Innovative Stewardship: Representing New Mexico to the World

“Some people are under the impression that we’re an art museum,” says Tony Chavarria, curator of ethnology at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture. “But particularly in Native pueblo culture, art isn’t separate from everything else.”

Chavarria’s holistic perspective on the natural intersections of history, culture and everyday life is central to the mission of the museum he

represents. “Everything we do promotes the culture, lifeways and art of the Native people of the American Southwest. It’s even reflected in our name,” he says.

Those intersections also flow throughout the Museum of New Mexico system, whose diverse cultural resources represent both tangible and

intangible aspects of the state’s land and peoples. From contemporary art to ancient artifacts, cutting-edge research to items that reflect generational migrations and creations, our institutions engage audiences in the complexity of the New Mexican experience through time. They also work together to share our statewide story and its international significance with the world.

It’s a robust approach to conserving and communicating culture that includes exhibitions, access to rare archives and an array of educational

opportunities for the public. But creating and maintaining such programming is expensive.

“Private support through the Museum of New Mexico Foundation is critical to institutional stewardship of these resources,” says Jamie Clements, Foundation president and CEO. “When people learn about the innovative ways that our divisions are utilizing these resources, it’s a compelling reason to give.”

Excellence in Archaeology

The Museum of Indian Arts and Culture opened in 1987 to showcase the holdings of the Laboratory of Anthropology, a research library founded in 1927 that later became part of the Museum of New Mexico. While the museum hosts fantastic exhibitions about Native lifeways, like its permanent display of Here, Now and Always, as well as eye-catching contemporary exhibitions like Painted by Hand: The Textiles of Patricia Michaels, Chavarria explains, “About 99 percent of our collections are archaeological, because we’re the mandated repository for materials that are being excavated in the state. There’s treasure as well as soil samples, rocks and things like that.”

The museum collaborates closely with the Office of Archaeological Studies, where Thatcher Seltzer-Rogers heads up a world-renowned

ceramic analysis laboratory. Seltzer-Rogers says that pottery fragments from the museum’s archaeological collection “are vital to understanding the development of complex societies in the Southwest. Analyzing broken pots allows me to investigate intriguing questions, from identifying ethnic groups, to how they exchanged materials and ideas, to how they learned to shape and paint pots.”

The Office of Archaeological Studies conducts research projects statewide. It also provides ethnographic and historical research services through five specialized laboratories, including one for low-energy plasma radiocarbon sampling, which is considered the most precise dating system in use worldwide. While rooted in New Mexico archaeology, all lab research has global educational value, often attracting international clients.

The Heart of Creation

Folk art collector and philanthropist Florence Dibell Bartlett founded the Museum of International Folk Art in New Mexico because folk art is understood and respected among local communities whose own folk art practices and traditions span centuries.

“In the museum world, it can be a struggle to get across how folk art is related to the fine art world. An exhibition of pottery or rugs can require weeks of additional educational programming,” says deputy director Laura Mueller. “We don’t have that baggage. We get to move immediately into the heart of what people have created.”

As a result, the museum seamlessly engages both local and global folk art as traditions with international meaning. For example, Mueller co-curated Amidst Cries from the Rubble: Art of Loss and Resilience from Ukraine, on view in the museum’s Gallery of Conscience until April 2025. Works are by artists and others who turned to art to process Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Shipping art out of a war zone

required creative international delivery routes and artistic flexibility. To get her mixed-media fiber painting through customs, one artist removed 200 found bullet casings, located a U.S. source for the same casings, and then re-created the piece at the museum just days before the exhibition opened.

“We’re talking about life, death and destruction in a war that’s currently being fought,” Mueller says. “The exhibition is hard-hitting. But we don’t want people to walk out feeling helpless. These works are amazingly beautiful, and they convey hope—a reason to continue to fight for what you believe in and to move forward.”

Closer to home, the museum is a repository for a wealth of New Mexican and American folk art. The collections staff recently took on oversight of 3,000 pieces of religious art, textiles, furniture and other objects held at the Taylor-Mesilla Historic Site in southern New Mexico, which is slated to open in fall 2025.

“The objects help us understand and appreciate the history, culture, and traditions of Mesilla and the Southwest borderlands,” says Charlie Lockwood, the folk art museum’s executive director. “We’re excited about potential collaborations with historic sites and other local partners that feature this remarkable collection, assembled and cared for by J. Paul and Mary Daniels Taylor and the Taylor family over many decades.”

The state’s eight historic sites offer opportunities to walk in the footsteps of important cultural figures while learning about multiple historical eras in New Mexico that often influenced world history and events. All the sites offer self-guided and ranger-guided tours, creative activities, seasonal festivals and natural beauty via hiking trails. Some even offer summer camp programs for kids, turning history from a school subject into an immersive experience.

Connecting through Collections

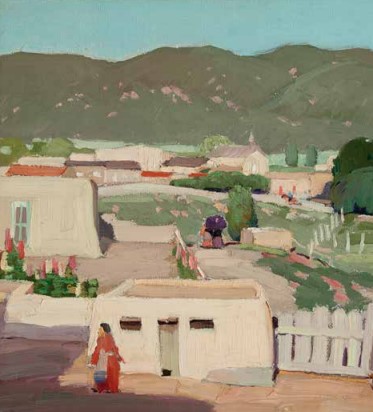

The New Mexico Museum of Art also houses a collection that is simultaneously hyperlocal and boundlessly international. Many of the museum’s original artists were modernists with global reputations.

“We think of so many of these artists as ‘our folks,’ like Gustave Baumann or Eugenie Shonnard. But, at least for the last century, New Mexico has been a national and international destination for artwork,” says Christian Waguespack, head of curatorial affairs and curator of 20th century art. “A lot of it is religious material—santero traditions from Mexico—but when it landed in New Mexico, it evolved into its own distinctive visual style.”

Though the museum does not focus on collecting traditional santos, a current exhibition engages stories of New Mexico’s cross-cultural pollination with the international narrative of New Spain. Visitors can dive into the topic in Saints & Santos: Picturing the Holy in New Spain, on view at the museum’s downtown Plaza Building through January 2025. Waguespack adds that Shonnard, a sculptor who donated her Santa Fe home and studio to the Museum of New Mexico Foundation, was a favored student of Alphonse Mucha, the father of art nouveau. From Mucha to Manga, an upcoming traveling exhibition of alternative art genres that he influenced, will be on view at the Vladem Contemporary in summer 2025, paired with a Shonnard exhibition at the Plaza Building.

“I never thought there would be an opportunity to show someone like Mucha at the New Mexico Museum of Art, but the more we understand our collection, the more connections we can make,” Waguespack says.

Waguespack’s first stop when researching New Mexico artists is the museum’s library and archives, which is a repository for artists’ journals

and correspondence, among other items. His next research avenue is the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives at the New Mexico History Museum, which contains close to a million photographs, negatives, prints and digital images. He never knows when he’ll stumble onto new information, because the archive always reveals new treasures.

“We only have estimates on the total number [of holdings], because not everything is catalogued,” says photo archives curator Hannah Abelbeck. Although databases are digital, input is manual and quite detailed. A perpetual backlog of uncatalogued items haunts every museum curator throughout the Museum of New Mexico system. The issues are usually staffing, time and funding.

“This is an area for which we need support,” says Chavarria of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture. “Often, funding for digitization and collections care must be raised. We’re getting more and more bequests from an era of collectors who are passing on, and these items just sit in storage instead of getting processed and given a permanent location.”

Community Memory

Located across from the Santa Fe Plaza, the New Mexico History Museum is a landmark for New Mexicans and a top destination for visitors from around the world. The institution is currently focused on utilizing one of the state’s most important cultural resources—the crucial memories held by people and communities that tell New Mexico’s most intimate stories.

“These are oral histories as well as physical objects, which can be as big as the Palace of the Governors or as small as a horn that’s been shaped to be a cooking ladle,” says the museum’s executive director Billy Garrett. Reflections on History, on view through April 2025, is

a photography exhibition that challenges visitors to transcend the boundary between past and present. “I wanted people to see themselves within history, so mirrors are incorporated into the space that allow you to project yourself into the images,” says deputy director Catherine Trujillo.

An ongoing exhibition, Palace Through Time, invites visitors to understand how the building has changed over hundreds of years. Guests walk through a touchable, 20-foot time grid and eight 3-D printed models of the Palace as researchers believe it stood at 50-year increments, based on historical documents.

“We have sketched plans, verbal descriptions and rough outlines on a map. Some information goes back to 1650,” Garrett says. “It’s as close as you can get to time travel.”

“The collective history of all our institutions is vital to New Mexico’s future as a center for art and culture,” adds Foundation CEO Clements. “Members’ support today will make possible tomorrow’s innovation.”

This article and images are from the Museum of New Mexico Foundation’s Member News Magazine.

Connect